this was removed from the main blog on 26th July 2015

This is really three pages. The first page / PART 1, covers most of the theory given in my researches - which are VERY extensive and carries forward the work of this year's Nobel Prize winners - a long way forward.

This is really three pages. The first page / PART 1, covers most of the theory given in my researches - which are VERY extensive and carries forward the work of this year's Nobel Prize winners - a long way forward.

Plus in PART 2 it explains why many economists make many mistakes including that of not reading my researches in full and it attempts to explain why they make bad policy decisions. Seven examples of where mainstream economics has failed without good cause for failing, are given

In the APPENDIX at the end it explains why money is the preferred choice compared to Gold, Bitcoins etc, and why a Gold Backed Currency just will not do.

-------------------

PART 1

The reason why many economists are not reading when they should be reading - the wrong assumptions they are making and the basis of the researches done.

What Robert Shiller, and two others who have just earned the 2013 Nobel Prize for economics, have said and what I have written in my book covers much of the same ground, but my book goes much further. It looks more deeply at the practical side of things.

The Nobel Prize was awarded mostly for finding ways to monitor the gathering storm, which is basically inflating asset values in a low interest rate environment. My work already knew what that those indications were and the cause of them, which is the mis-pricing of debt; and it tries to put an end to the problem by preventing the storm clouds from growing - by the correct pricing of debt so as to preserve financial stability..

The Nobel Prize was awarded mostly for finding ways to monitor the gathering storm, which is basically inflating asset values in a low interest rate environment. My work already knew what that those indications were and the cause of them, which is the mis-pricing of debt; and it tries to put an end to the problem by preventing the storm clouds from growing - by the correct pricing of debt so as to preserve financial stability..

Thus, as far as I know, my draft book has information that is significantly more advanced than anything already published elsewhere. Some key parts of it are outlined below. Unfortunately the book is long and has taken years to write because it is so extensive in its implications that the proposals will change just about everything. So I missed out on that Nobel Prize.

BUT ALSO

It should be noted that our best educated economists seem to be unwilling to read and discuss my draft book because it has not yet been published with full peer reviews organised by a reputable publisher. But they know that it does have some excellent peer reviews here and elsewhere. In fact three people have said that it will become or should become a part of any university's curriculum.

I was surprised recently to receive an email from a Zimbabwean telling me that since the majority of review team members were the top Zimbabweans in economics, banking, and accounting then I must be right because he claims that Zimbabweans occupy a majority of key positions in the top 500 companies listed on the UK Stock Exchange.

That unwillingness to read and examine and discuss the material presented particularly goes for those who work at the IMF, the World Bank, the Fed, and The Bank of England. Then there are the top professors at the world's best universities to add to this list.

Is this filtering necessarily a good idea? That is only reading papers that are published in academic journals - papers are much shorter and faster to write and generally vastly less comprehensive. It does save them time reading some really crackpot stuff I suppose, but then, as stated, I do have excellent peer reviews from actuaries and professors just so as to ensure that I am ranked among those that have something of value to say.

What else may be putting them off?

I was surprised recently to receive an email from a Zimbabwean telling me that since the majority of review team members were the top Zimbabweans in economics, banking, and accounting then I must be right because he claims that Zimbabweans occupy a majority of key positions in the top 500 companies listed on the UK Stock Exchange.

That unwillingness to read and examine and discuss the material presented particularly goes for those who work at the IMF, the World Bank, the Fed, and The Bank of England. Then there are the top professors at the world's best universities to add to this list.

Is this filtering necessarily a good idea? That is only reading papers that are published in academic journals - papers are much shorter and faster to write and generally vastly less comprehensive. It does save them time reading some really crackpot stuff I suppose, but then, as stated, I do have excellent peer reviews from actuaries and professors just so as to ensure that I am ranked among those that have something of value to say.

What else may be putting them off?

Here is a list of some of the things that put some economists off.

Then there is this: I have become something of an economist by virtue of what I have read and observed and indeed achieved, over a lifetime. Also check out my unique achievements in investment management - FIG 4 onwards - something that academics, based upon the market efficiency theory put forward by Dr Fama, said was impossible at the time. I was able to prove that markets are not that efficient by consistently out-performing them. See Style A at right, below.

My ability to analyse was better than that of the market. Today Dr Fama admits that over the longer term markets are much more predictable, which is why I only altered my portfolio balances a couple of times a year in any major way.

I was able to steer clear of high risk investments at times when they were high risk. If you can do that then the only way is up. But it was almost 24/7 work. I picked brains and sorted out who had got the essential facts right and drew my conclusions.

2

EXAMPLE TWO I told a very senior economist in South Africa that I wanted to give a talk to his university. But when I told him that the way things are, the most unstable economic conditions occur when interest rates are low, he told me that this was counter-intuitive and he refused to listen any more. His viewpoint was that the lower the rate of inflation the more stable the economy becomes, which in some respects is true, and to an extent, that is as it should be.

EXAMPLE TWO I told a very senior economist in South Africa that I wanted to give a talk to his university. But when I told him that the way things are, the most unstable economic conditions occur when interest rates are low, he told me that this was counter-intuitive and he refused to listen any more. His viewpoint was that the lower the rate of inflation the more stable the economy becomes, which in some respects is true, and to an extent, that is as it should be.

The reason for saying what I said is basically the same reason why Robert Shiller, our latest Nobel Laureate, 2013, said the same thing about housing finance, although I was not aware of who was saying what at the time.

The reason why the developed economies can become more unstable than others is because lenders reduce the cost of borrowing as interest rates fall, not just by a little bit, but by a great deal. This enables a lot of people to buy houses and to borrow to invest in other things like businesses, people who were previously unable to afford those things. And those who already could afford those things could then afford to buy into the same things in a much bigger way.

The reason why the developed economies can become more unstable than others is because lenders reduce the cost of borrowing as interest rates fall, not just by a little bit, but by a great deal. This enables a lot of people to buy houses and to borrow to invest in other things like businesses, people who were previously unable to afford those things. And those who already could afford those things could then afford to buy into the same things in a much bigger way.

Unfortunately interest rates have a habit of rising after they have fallen. The speed with which the mortgage repayment costs then rise can be really scary, and that is when everything falls apart as Robert Shiller and I and many others have long pointed out.

Another point is that a half century of low inflation in the developed economies does allow a much larger proportion of people to own houses and to become borrowers. This is one reason why the developed nations have the largest home ownership sectors. Rental costs do not jump up and down but respond more to aggregate demand or shall we say, average incomes, which in terms of economic stability, fits in with the price movements of everything else. So those nations with larger rental sectors find that their economies are more stable. All prices and all spending patterns are more coherent which means that spending does not get diverted to and from the borrowing sectors as much, destroying and rebuilding the same jobs over and over.

Another point is that a half century of low inflation in the developed economies does allow a much larger proportion of people to own houses and to become borrowers. This is one reason why the developed nations have the largest home ownership sectors. Rental costs do not jump up and down but respond more to aggregate demand or shall we say, average incomes, which in terms of economic stability, fits in with the price movements of everything else. So those nations with larger rental sectors find that their economies are more stable. All prices and all spending patterns are more coherent which means that spending does not get diverted to and from the borrowing sectors as much, destroying and rebuilding the same jobs over and over.

If the inflation rate and the interest rates had been higher in the developed economies, then those loans would have been smaller, the housing sector would have been smaller, and a rise in the rate of interest would have caused a smaller percentage increase in the cost of the repayments. When inflation levels are higher, incomes soon rise enough to overcome that difficulty of rapidly risen mortgage costs. This is why it was the developed, low interest rate economies, that have been the hardest hit. That senior economist was wrong and missed a good opportunity to have my researches heard.

The first nation to experience the most severe consequences of sustained low interest rates in my living memory was Japan. Now it is the USA and Europe. The Japan experience led me to write about what I call The Low Inflation Trap, some years before 2008, because it is a situation from which it is difficult for an economy to recover – interest rates have to return to normal if recovery is to be well established and, given the sensitivity to interest rates that we have decided to build into our debt structures (mortgages and bonds), that is a steep hill to climb.

The first nation to experience the most severe consequences of sustained low interest rates in my living memory was Japan. Now it is the USA and Europe. The Japan experience led me to write about what I call The Low Inflation Trap, some years before 2008, because it is a situation from which it is difficult for an economy to recover – interest rates have to return to normal if recovery is to be well established and, given the sensitivity to interest rates that we have decided to build into our debt structures (mortgages and bonds), that is a steep hill to climb.

This is why the developing world has been barely touched by the crisis except by the fallout from their customers, the developed economies, who are no longer able to buy as much of their products; and added to that there is the fallout from the instability built into currencies through some kind of mis-pricing linked to massive investment flows and hot money flows..

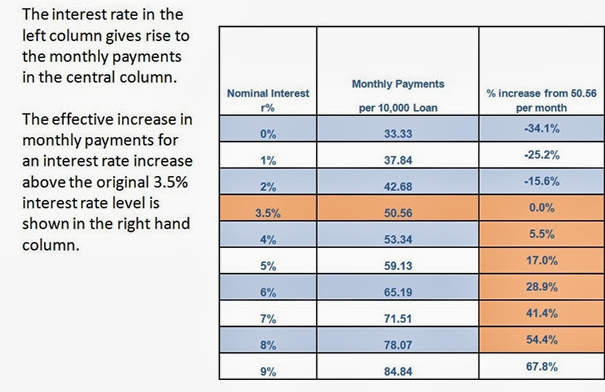

Here is the evidence for what I have just written about interests rate sensitivity.. It is simple maths – the way that lenders calculate the repayment costs and the way that feeds into the story that I have just told. The table reflects the 3.5% low point in USA mortgage rates and the 8% or so target that the Fed had in mind to slow inflation and then normalise the interest rate at closer to 7% - the level that I predicted at the time based on the reasoning given in that linked page.

You can see the 54% increase in mortgage costs right there in FIG 1. Maybe the Fed does not use these tables.

FIG 1 - Monthly mortgage costs v nominal rates of interest

Source: Edward C D Ingram Spreadsheets

Just this week, Mid October 2013, economist Peter Spencer and the UK Treasury have joined forces to say that UK house prices are not inflated – yet they are still using these low interest rates and house prices have topped the level reached in 2008! Readers may disagree with the UK Treasury and Peter Spencer. I know I do. And Robert Shiller has just announced that his crisis indicator is again flashing red in the USA where interest rates are similarly low. Perhaps the UK people are predicting no end to low interest rates - which would seem to be a precondition to saying that property prices are not inflated.

FIG 2 - USA House Prices

This is how house prices changed in the USA. In 1980 USA inflation and interest rates were very high, and we see in this chart the way that house prices recovered as they became more normal at the end of that decade. And we see how they inflated as interest rates continued to fall and stay down thereafter. It is a pity that the graph is not adjusted for average incomes because mortgages are measured in multiples of income. The lower the rate of interest, the higher the multiple that gets lent by our current lending models.

But over that period USA median incomes were not changing much so he graph may not need a lot of adjustment for that. The wage / income increases were mostly going to the top 1%. So the graph more or less accidentally shows how the price of houses has risen compared to median incomes, which can best be explained by an increase in the income multiple being lent for housing finance as nominal interest rates fall.

But over that period USA median incomes were not changing much so he graph may not need a lot of adjustment for that. The wage / income increases were mostly going to the top 1%. So the graph more or less accidentally shows how the price of houses has risen compared to median incomes, which can best be explained by an increase in the income multiple being lent for housing finance as nominal interest rates fall.

3. EXAMPLE THREE When I say that an economy is supposed to be able to ‘float’ on inflation and that inflation is not supposed to do much harm, mainstream economists just think I am crazy.

What I am saying is this:

If we want our economies not to be distorted by a changing rate of inflation, (of incomes, not prices please because rising incomes are what drives prices higher than they otherwise would be), then we would want all prices of everything to increase proportionately. That includes all wealth to be stored as savings in a supposedly safe place; where they can rise proportionately to match that increase in the level of aggregate demand caused by those rising incomes.

This statement comes as a surprise to most economists and ordinary people because we are all taught to think that wealth is what we can buy and so keeping pace is prices related. You keep your purchasing power and you keep your wealth. What has been overlooked is that the purchasing power of everyone else is rising as incomes rise faster than prices, so you are actually being lft behind. Your share of the national wealth is falling. If you had invested in almost anything else your investment growth rate would have a link to rising incomes, as do rentals and property prices. So if we want to keep a balanced spending pattern and balanced wealth we have to use average incomes as the base line for measurement.

What we need to do is to ensure that all incomes and all spending and all wealth is able to rise proportionately when average incomes rise. If they are able to do so then what remains is market forces (as usual on individual items) and time delays. This ability to keep pace with rising incomes is a precondition to there being no forced disturbance to spending patterns that would threaten current employment and production patterns. But the table above for mortgage costs defies that norm - it prevents that from taking place in a key sector of the economy.

When we talk of prices inflation we are looking at prices falling less quickly than they might have fallen if average incomes had not risen. Or if prices are rising then that rise would be faster the faster average incomes were rising because average incomes are the source of demand. All prices adjust to match supply with demand - or that should be the case if we want spending patterns and employment patterns in the economy to remain unaffected by rising or falling incomes.

Only if that proportionate adjustment to rising aggregate demand happens across the board will spending patterns be able to remain the same, jobs remain the same, or at least not affected by this, and if that happens, then the economy will be able to float on the varying rate of incomes inflation / aggregate demand, without distortions and without creating unemployment in the process of adapting to the changing rate of incomes inflation / aggregate demand in the domestic economy. We can deal with currencies and international trade later.

How to ensure that this can happen and how to ensure that to a large extent it does happen is what readers of my draft book and the linked mathematics will discover.

This statement comes as a surprise to most economists and ordinary people because we are all taught to think that wealth is what we can buy and so keeping pace is prices related. You keep your purchasing power and you keep your wealth. What has been overlooked is that the purchasing power of everyone else is rising as incomes rise faster than prices, so you are actually being lft behind. Your share of the national wealth is falling. If you had invested in almost anything else your investment growth rate would have a link to rising incomes, as do rentals and property prices. So if we want to keep a balanced spending pattern and balanced wealth we have to use average incomes as the base line for measurement.

What we need to do is to ensure that all incomes and all spending and all wealth is able to rise proportionately when average incomes rise. If they are able to do so then what remains is market forces (as usual on individual items) and time delays. This ability to keep pace with rising incomes is a precondition to there being no forced disturbance to spending patterns that would threaten current employment and production patterns. But the table above for mortgage costs defies that norm - it prevents that from taking place in a key sector of the economy.

When we talk of prices inflation we are looking at prices falling less quickly than they might have fallen if average incomes had not risen. Or if prices are rising then that rise would be faster the faster average incomes were rising because average incomes are the source of demand. All prices adjust to match supply with demand - or that should be the case if we want spending patterns and employment patterns in the economy to remain unaffected by rising or falling incomes.

Only if that proportionate adjustment to rising aggregate demand happens across the board will spending patterns be able to remain the same, jobs remain the same, or at least not affected by this, and if that happens, then the economy will be able to float on the varying rate of incomes inflation / aggregate demand, without distortions and without creating unemployment in the process of adapting to the changing rate of incomes inflation / aggregate demand in the domestic economy. We can deal with currencies and international trade later.

How to ensure that this can happen and how to ensure that to a large extent it does happen is what readers of my draft book and the linked mathematics will discover.

THE UNRECOGNIZED PROBLEM

Well that is an ideal, but the whole purpose of writing this book is to demonstrate why we are not able to get close to that ideal. It is because our debt structures, like the way we manage mortgages and mortgage costs for example, distort that pattern of response. Whereas rentals follow the expected pricing pattern, mortgage costs do not. Whereas the cost of a haircut follows that pattern of rising value / cost, the value and cost of a fixed interest debt does not follow that pattern. It stays rigidly fixed as if nothing was going on. The value falls as incomes rise and no one can forecast by how much that will be over a long period. No valuation with any stable meaning can be done.

What this resume shows is that when average incomes increase, the price of everything should rise, and that means that the value of money has fallen proportionately. Rather than trying to prevent that from happening we need to be able to make proportionate adjustments for it.

What this resume shows is that when average incomes increase, the price of everything should rise, and that means that the value of money has fallen proportionately. Rather than trying to prevent that from happening we need to be able to make proportionate adjustments for it.

There is a very short list of things that we need to be put right.

FIRST PROBLEM

The first one is the way that lenders calculate the cost of borrowing and how much they are willing to lend based on those calculations. As the FIG 1 above shows, there is no relationship between the cost of a mortgage and the level of aggregate demand / average incomes, as there is with the cost of rentals.

Mortgage costs move up and down extremely fast. This creates major distortions and property price bubbles and it creates vulnerable lenders and vulnerable home owners and businesses. It changes spending patterns. And it moves wealth from some sectors to other sectors as loan servicing costs and loan sizes vary, making property prices vary. Then the wealth effect clicks in and out, and businesses boom and bust in response. An increasing number of economists, including Robert Shiller and at least one at the BIS are saying, as I have done for decades, that recessions and major financial crises, are born out of this.

This book shows that it is possible to redesign the costing of mortgage finance in a way that leaves market forces in play and without distorting the response to changes in incomes inflation and aggregate demand.

Mortgage costs move up and down extremely fast. This creates major distortions and property price bubbles and it creates vulnerable lenders and vulnerable home owners and businesses. It changes spending patterns. And it moves wealth from some sectors to other sectors as loan servicing costs and loan sizes vary, making property prices vary. Then the wealth effect clicks in and out, and businesses boom and bust in response. An increasing number of economists, including Robert Shiller and at least one at the BIS are saying, as I have done for decades, that recessions and major financial crises, are born out of this.

This book shows that it is possible to redesign the costing of mortgage finance in a way that leaves market forces in play and without distorting the response to changes in incomes inflation and aggregate demand.

SECOND PROBLEM

The second problem to address is fixed interest bonds. Fixed interest bonds, by definition, are not allowed to make any adjustment for variations in the rate at which money falls in value.

Fixed interest debt by definition is a form of wealth for one party and a call on the income of the other party. Use of fixed Interest is a part of the agreement that defines what bonds are. But being fixed interest, when incomes inflation takes a hand, the value of the bond and the cost of the bond are both deeply affected, especially if the repayment term is a long period like ten years or more; even five years in some cases can be a long time if inflation rates are high and/or just changeable.

Fixed interest debt by definition is a form of wealth for one party and a call on the income of the other party. Use of fixed Interest is a part of the agreement that defines what bonds are. But being fixed interest, when incomes inflation takes a hand, the value of the bond and the cost of the bond are both deeply affected, especially if the repayment term is a long period like ten years or more; even five years in some cases can be a long time if inflation rates are high and/or just changeable.

So this unbalances wealth, activates the wealth effect, and it unbalances the budgets of the borrowers, particularly if incomes rise less quickly than had been hoped or if incomes start to fall. That leads to a reduced overall income and an even more reduced net spendable income after the fixed cost payments have been paid. This can easily happen for a business and it can happen for a government if a country goes into a recession or a period of austerity.

The induced wealth effect always adds positive (re-enforcing) feedback to the economic cycle. As interest rates fall bonds add value and property prices follow suit, creating a wealth effect on spending and credit creation - increasing money supply. And when interest rates rise everything reverses and the wealth effect reverses as well.

Robert Shiller and I are saying that fixed interest borrowing can be too costly, and it hits at the worst possible time - when the rate of increase in incomes is slowing or worse still, is turning negative. That then makes government borrowing much more costly at the worst possible time.

It makes it very expensive for tax payers / governments needing to try to balance its books in such times if their debt servicing costs remain the same in money terms during a slowdown or a recession. And not just be a little bit. The figures are amazingly costly in some cases that are illustrated in the book. Yet no one seems to have noticed that this is something that we designed into the economic structure and that we did not need to do that.

In the book illustration it was shown that the USA government was paying around nine times as much in wealth transfer payments to investors in its fixed interest bonds in 1980 than it needed to pay, and the reason was not that there was a recession, which is the problem now in Europe. The problem was that they were getting a handle on, and reducing the rate of inflation.

So fixed interest bonds destabilise wealth for both parties - lender and borrower. And that destabilises the whole economy. I think Dr Shiller overlooked that one.

Instead of using fixed interest rates I have suggested using index-linked bonds, linked to aggregate demand in some way, such as Average Earnings / Incomes Growth (AEG% p.a.). It works both ways: if the economy prospers the cost of servicing this kind of index-linked debt rises in money terms but not in terms of value or revenues (much). The result for investors is that their share of the national wealth is protected and if the nation is getting poorer or richer they are just a normal part of the community, also getting richer or poorer. It keeps everyone in the same boat and it keeps spending and wealth proportionate. It protects the economy. It protects employment. Investors are not left behind and they are not overtaking or privileged.

Whereas Professor Shiller suggests that governments index link their debt to nominal GDP, and whereas he says that the bonds will be somewhat volatile, I am not so sure. It is a whole lot better than fixed interest bonds and as we have both pointed out, it would have benefited the Greek people significantly during their period of austerity. But why would such bonds be volatile?

Professor Shiller says it is to do with the varying prospects for economic growth. That may affect demand from foreign investors to some extent but less so for domestic institutional investors who liabilities tend to be linked to the average incomes of their clients. For example, pension funds. This is why I have been at pains to say that there is a debate to be had on this issue of what index we should link to. I have a chapter on that ready to place in my draft book.

The basic point is that such bonds have to be structured to sell - to be of use. So whereas the government's revenues may have a link to GDP which would favour using that GDP index, pension funds and other investments all have a link to average incomes growth rates. And they often need a higher cash flow than just a 1% coupon on a GDP-linked bond. Thus Dr. Shiller still has some homework to do.

And it also raises the question of how the value of such bonds and the income on offer is measured. Should it be measured against prices? Certainly not.The reason for saying that is well and extensively explained in my draft book, which mainstream economists do not want to read! And in this latest revision I have explained this in outline above.

It is a tricky subject and it took me years to convince myself that my arguments were sound. But now I am very confident that they are sound. Furthermore, again, as I just wrote, if a market for index-linked bonds is to be opened wide, then the bonds have to be saleable to investors that are looking to make comparisons with other forms of investment that are already loosely linked to AEG - for example, property and equities. And they have to be useful in minimising risk for pension funds and annuities both of which are needing to deliver an income-related product to their clients.

Economists are seeking a risk free interest rate measure. There is no such thing unless you are interested in protecting money assets using fixed interest bonds and you are not interested in protection of wealth. But AEG-linked Bonds (linked to Average Earnings Growth) can come very close to what is needed. I call them 'Wealth Bonds'.

Hmm I already wrote this - but here I add something.

The wealth bonds that I suggested are also fine for funding mortgages, not just government debt. And one thing that I suggest that Professor Shiller adds to his papers is that investment managers do not like low income investments such as his Trills, which are bonds linked to GDP. I explain that and the way to deal with it in my book and in the awaited chapter entitled NEW FINANCIAL PRODUCTS RESULTING.

.

The induced wealth effect always adds positive (re-enforcing) feedback to the economic cycle. As interest rates fall bonds add value and property prices follow suit, creating a wealth effect on spending and credit creation - increasing money supply. And when interest rates rise everything reverses and the wealth effect reverses as well.

Robert Shiller and I are saying that fixed interest borrowing can be too costly, and it hits at the worst possible time - when the rate of increase in incomes is slowing or worse still, is turning negative. That then makes government borrowing much more costly at the worst possible time.

It makes it very expensive for tax payers / governments needing to try to balance its books in such times if their debt servicing costs remain the same in money terms during a slowdown or a recession. And not just be a little bit. The figures are amazingly costly in some cases that are illustrated in the book. Yet no one seems to have noticed that this is something that we designed into the economic structure and that we did not need to do that.

In the book illustration it was shown that the USA government was paying around nine times as much in wealth transfer payments to investors in its fixed interest bonds in 1980 than it needed to pay, and the reason was not that there was a recession, which is the problem now in Europe. The problem was that they were getting a handle on, and reducing the rate of inflation.

So fixed interest bonds destabilise wealth for both parties - lender and borrower. And that destabilises the whole economy. I think Dr Shiller overlooked that one.

Instead of using fixed interest rates I have suggested using index-linked bonds, linked to aggregate demand in some way, such as Average Earnings / Incomes Growth (AEG% p.a.). It works both ways: if the economy prospers the cost of servicing this kind of index-linked debt rises in money terms but not in terms of value or revenues (much). The result for investors is that their share of the national wealth is protected and if the nation is getting poorer or richer they are just a normal part of the community, also getting richer or poorer. It keeps everyone in the same boat and it keeps spending and wealth proportionate. It protects the economy. It protects employment. Investors are not left behind and they are not overtaking or privileged.

Whereas Professor Shiller suggests that governments index link their debt to nominal GDP, and whereas he says that the bonds will be somewhat volatile, I am not so sure. It is a whole lot better than fixed interest bonds and as we have both pointed out, it would have benefited the Greek people significantly during their period of austerity. But why would such bonds be volatile?

Professor Shiller says it is to do with the varying prospects for economic growth. That may affect demand from foreign investors to some extent but less so for domestic institutional investors who liabilities tend to be linked to the average incomes of their clients. For example, pension funds. This is why I have been at pains to say that there is a debate to be had on this issue of what index we should link to. I have a chapter on that ready to place in my draft book.

The basic point is that such bonds have to be structured to sell - to be of use. So whereas the government's revenues may have a link to GDP which would favour using that GDP index, pension funds and other investments all have a link to average incomes growth rates. And they often need a higher cash flow than just a 1% coupon on a GDP-linked bond. Thus Dr. Shiller still has some homework to do.

And it also raises the question of how the value of such bonds and the income on offer is measured. Should it be measured against prices? Certainly not.The reason for saying that is well and extensively explained in my draft book, which mainstream economists do not want to read! And in this latest revision I have explained this in outline above.

It is a tricky subject and it took me years to convince myself that my arguments were sound. But now I am very confident that they are sound. Furthermore, again, as I just wrote, if a market for index-linked bonds is to be opened wide, then the bonds have to be saleable to investors that are looking to make comparisons with other forms of investment that are already loosely linked to AEG - for example, property and equities. And they have to be useful in minimising risk for pension funds and annuities both of which are needing to deliver an income-related product to their clients.

Economists are seeking a risk free interest rate measure. There is no such thing unless you are interested in protecting money assets using fixed interest bonds and you are not interested in protection of wealth. But AEG-linked Bonds (linked to Average Earnings Growth) can come very close to what is needed. I call them 'Wealth Bonds'.

Hmm I already wrote this - but here I add something.

The wealth bonds that I suggested are also fine for funding mortgages, not just government debt. And one thing that I suggest that Professor Shiller adds to his papers is that investment managers do not like low income investments such as his Trills, which are bonds linked to GDP. I explain that and the way to deal with it in my book and in the awaited chapter entitled NEW FINANCIAL PRODUCTS RESULTING.

.

Ditto here - I already wrote this above. But is is a useful reminder:

All we need to do is to index-link those debts to the incomes inflation / deflation as the case may be, so as to take out the fixed interest bond distortion. Such distortions end up creating unemployment because they change wealth and spending patterns. The proportion of income spent by people whose wealth rises as their bonds rise in value changes; and vice versa if their wealth reduces. It is what economists call the ‘wealth effect’. The proportion of a government, a business, or a home buyer’s revenues or incomes that goes into servicing their debts falls when fixed rates are imposed, as incomes inflation takes their revenues / incomes higher and vice versa if there is deflation.

All we need to do is to index-link those debts to the incomes inflation / deflation as the case may be, so as to take out the fixed interest bond distortion. Such distortions end up creating unemployment because they change wealth and spending patterns. The proportion of income spent by people whose wealth rises as their bonds rise in value changes; and vice versa if their wealth reduces. It is what economists call the ‘wealth effect’. The proportion of a government, a business, or a home buyer’s revenues or incomes that goes into servicing their debts falls when fixed rates are imposed, as incomes inflation takes their revenues / incomes higher and vice versa if there is deflation.

If fixed interest bonds are used, that also changes long term plans and spending patterns at every level of the economy. At a government level falling gross revenues can seriously impact on net revenues when debt servicing costs remain fixed, and commitments made to support social services of one kind or another can become unaffordable. For people planning their retirement, there is no way that using fixed interest bonds can provide a safe, risk free investment that can keep pace with rising incomes / incomes inflation. But there could be if such bonds were index-linked to national revenues, average incomes, or GDP. Any one of those indices would be a better bet than fixed interest bonds.

THE OBJECTIVE

So in this book we will be looking at this and also at how and why we can arrange mortgage and business and government finance in ways that take out the financial instability from the participants and thus from the whole economy. In effect each party, each lender / investor and borrower forms a contract which protects the wealth and the budget of the other parties. That way, inflation of incomes can go any direction at any time and it has little impact on any party, lender, borrower, or saver / investor.

AGGREGATE DEMAND OR (AEG) CAN BE A FORM OF INFLATION

I introduce the concept of aggregate demand – the total spending in the economy as being somehow related to incomes – the total of all incomes, say GDP, or the average income could be another proxy for this – the rate of change of aggregate demand being what we are looking at. In this book. I mostly use the proxy of Average Earnings / Incomes Growth, AEG, because what we earn eventually gets spent by someone – ourselves if we spend it and others if we save it and then it gets lent.

Some economists have just stopped reading the moment they see I am using a ‘wrong index’ as they see it. That happened with one economist when I discussed using a link to GDP. The objection was that GDP figures can be manipulated. Well anything can be manipulated.

Different definitions may be needed in some circumstances. For example, there is little relationship between average incomes growth in America and median incomes growth. But this does not mean that we should use what could be described as a fixed interest rate index (fixed interest) bond instead! What it means is that we need to be careful how we define an index and what its purpose is going to be.

Different definitions may be needed in some circumstances. For example, there is little relationship between average incomes growth in America and median incomes growth. But this does not mean that we should use what could be described as a fixed interest rate index (fixed interest) bond instead! What it means is that we need to be careful how we define an index and what its purpose is going to be.

If prices are free to rise and fall in response to aggregate demand and are all going to change at least somewhat proportionately compared to what they would otherwise have been, then a changing rate of incomes inflation, AEG, will neither re-distribute wealth through volatile asset prices, nor force a change to spending patterns. Wealth and spending and prices and incomes will all stay in harmony – more or less, whereas at present mortgages and property prices, bonds and government spending and business plans, and even interest rates, are all knocked off centre by such changes to the rate of incomes inflation, AEG% p.a.

The book deals with the link between interest rates and AEG in some detail. At present, the economy cannot float on inflation because the waves caused by these distortions flood the decks of the economic ship which is not designed to float on aggregate demand levels whatever they may be, but instead the economic ship (mortgage repayments and bonds) is designed to resist changes in the value of money. And all of the interest on savings is taxed, and it all gets tax relief on the supposition that money has a constant value. Contracts are given in ‘protect my money’ terms so we have to prevent inflation from happening. Unfortunately like a tree that cannot bend in the wind, it is liable to break because we cannot fix the value of money. The value of money is negotiable between the spender and the recipient, and always will be. The quantity of money needed is always unknown - there is never enough data for policy makers to identify how much money supply there should be and the velocity of circulation is never fixed.

We need a way of rising these waves, not resisting them.

Some economists say we should link the value of money to gold. That does not solve any of those problems. It just adds another variable to be managed - the price of gold is itself a variable.

I have written about that in a short piece that I will add as the appendix (below) and maybe I will create a new page for it on a blog because it is well liked. One reader wrote that it encapsulates everything about currency and another wrote something similar in much stronger terms.

We need a way of rising these waves, not resisting them.

Some economists say we should link the value of money to gold. That does not solve any of those problems. It just adds another variable to be managed - the price of gold is itself a variable.

I have written about that in a short piece that I will add as the appendix (below) and maybe I will create a new page for it on a blog because it is well liked. One reader wrote that it encapsulates everything about currency and another wrote something similar in much stronger terms.

PART 2

WHY WE NEED A RE-THINK

ECONOMISTS SOMETIMES SCARE ME

Earlier I mentioned that I am not a trained economist. I am more of an engineer. I used to apologise for that, but then people would tell me not to apologise. They told me that some of the best economists we have were once engineers.

From what I have seen of what is taught nowadays and what credentials you need to get a top job in policy making, I am not just unimpressed, I feel scared. Look at the way they behave. They are trying to formulate complex mathematical models so as to forecast what will happen and then they try to manage the symptoms. That process can go wrong in two ways –

A. The forecast can be wrong, so wrong that almost anyone that is not an economist can see that it is wrong.

B Policy makers can do stupid and unexpected things

Example A. When the Fed raised interest rates by 4.25% every estate agent in the land could smell disaster, and anyone with common sense knew that low interest rates were stoking asset prices and that this would reverse causing harm. It did not take Robert Shiller to point that out – it is common sense. But economists are so impressed that he put it in writing that they gave him a Nobel Prize. Wow what else can we ordinary folk write that may earn us such a prestigious prize?

Example B. There was a time in the UK when I knew there was going to be inflation because they were holding interest rates too low for too long. 200 economists sent a petition to the treasury warning them. But the treasury, the trusted policy makers, said otherwise. Eventually the time came when inflation was about to take off. I saw that clearly because school leavers were commanding salaries about twice as much as a few years earlier and they were buying houses that were still depressed in value with ease. The surplus stock of unsold houses was vanishing fast. So I got an appointment to see Peter Lilley at his office in the Treasury. He had a title like ‘Chief Secretary to the Treasury’ at the time. He did not listen. He lectured. He said that there is now a strong correlation between M0 and inflation. So if we manage M0 we manage inflation. A few weeks later inflation took off. Later I was asked by the Treasury how I had known.

Example C There was the time when oil prices fell to $11 a barrel in the 1980s. Mainstream economists were unanimous in the opinion that the stock market would now boom and economic growth would accelerate. They did not think beyond their models. They forgot to think what would happen when oil revenues dropped. When that happened it changed spending patterns. The big spenders withdrew. There was a slowdown as I had said there could be.

Example D There was the time at the start of the 1990s when the UK policy was to keep the exchange rate firm presumably as a way of managing inflation. It was actually destroying exports and slowing the economy. Fortunately George Soros came to the rescue and delivered a blow to the exchange rate which sorted that out. I was so relieved and I immediately switched my investment emphasis accordingly – the stock market recovered and so did the economy.

Example E It took a long time for economists to understand that when the cost of imports rises it is not a sign that interest rates should rise. Yes it increases the rate of inflation, but that is not the same thing as increasing the demand for money and it is not a reason to slow the economy. To me this was obvious from the start. External factors such as the rising price of oil cannot be addressed in this way. It has taken a few decades for those economists to get an understanding. What are they being taught? It is amazing.

Example F I was not at all surprised that the so called Keynesian stimulus of 2008/9 failed. When there is an excess of debt and people's main concern is to unload it and when there is the kind of instability that is linked to the Low Inflation Trap, there is no way to build the confidence or the momentum needed to create an economic recovery. As I said in my recorded lecture to NUST - my local university, at the time, this is a high risk strategy. If it fails then the situation will be worsened. And that is what happened.

Example G In the latest quarterly bulletin from the Federal Reserve Bank and in a similar paper from the FRBSF (San Francisco Fed) there is bewilderment - a confession of ignorance. But are they willing to listen to another voice? No. They even wrote to me saying so. They continue to try to find measurements like instruments set down to forecast an earthquake. They have no idea how to prevent the earthquake - they are looking for ways to evacuate and to suppress, but not to take away the cause.

Example F I was not at all surprised that the so called Keynesian stimulus of 2008/9 failed. When there is an excess of debt and people's main concern is to unload it and when there is the kind of instability that is linked to the Low Inflation Trap, there is no way to build the confidence or the momentum needed to create an economic recovery. As I said in my recorded lecture to NUST - my local university, at the time, this is a high risk strategy. If it fails then the situation will be worsened. And that is what happened.

Example G In the latest quarterly bulletin from the Federal Reserve Bank and in a similar paper from the FRBSF (San Francisco Fed) there is bewilderment - a confession of ignorance. But are they willing to listen to another voice? No. They even wrote to me saying so. They continue to try to find measurements like instruments set down to forecast an earthquake. They have no idea how to prevent the earthquake - they are looking for ways to evacuate and to suppress, but not to take away the cause.

Re Example E - Any engineer that knows his control systems theory knows that you have to apply your force to the right target, in the right amount, and at the right time.

So the worry is that our economists get so deeply immersed in what they are taught and the correlations that they are seeking that they forget all about common sense. The Fed certainly did. And many still believe the crisis was about Sub-prime and other issues! That was the icing of the devil’s cake. We are still left with the cake and the question of how to deal with restoring interest rates back to their normal value of closer to 7% for housing finance, and other rates for other debts.

Do economists know what normal is? I don't think so, so as I already mentioned, I give some guidance in the book. The formula gave an accurate prediction in 2004 of where interest rates should be in the USA to curb inflation and the level that the Fed would aim at was just above that 7% interest rate figure (for housing finance with other rates finding their own proportionate levels), as has to be the case, in theory, to deliver the slow down. That will only work if the raise does not crash the whole economy....if the mortgage model in use does not crash the whole economy and the bond values do not crash too as they will and as they did. The problem remains.

If interest rates rise that much then mortgage costs and the value of bonds will change dramatically, maybe rising by 50% for mortgages and falling by something similar for long dated bonds.

If interest rates rise that much then mortgage costs and the value of bonds will change dramatically, maybe rising by 50% for mortgages and falling by something similar for long dated bonds.

As we can now see, economists are not taught what goes on at ground level – at the level of the financial products and services that are on offer – and what difficulties they, (mortgages and bonds in particular), may cause, nor how to address those problems. They are trying to manage the unruly symptoms that are thrown at them from those sources instead of addressing the source of the problems. This is the scary part.

In this book we look at the sources of financial instability, and we do not try to manage the symptoms because if we remove the source, then those symptoms will just go away. And there are dozens and maybe hundreds of them.

But when I say that to economists they just look baffled.

Economists just tell me that economies do not work in that smooth and well behaved way (which is true – they are much too distorted to make human behaviour predictable) and they tell me that you cannot predict people’s behaviour.

So I ask, ”Is it any wonder that you cannot predict people’s behaviour when your own behaviour is so unpredictable and the way product providers and regulators have designed the financial services that everyone is forced to use ensures that people, businesses and governments, can neither protect their wealth nor their budgets?”

And the fact that they are trying to mange the symptoms without understanding the causes, I find to be a bit scary. I say that the science of economics has yet to be written – it starts with finding ways to allow prices to adjust and to balance the supply of everything with the demand for everything. In short, prices are there to vary, and in doing so, to enable the economy to find a balance and to keep that balance.

Only then, after we have fixed those problems, can we ask, "What else do we need to do to enable sustained economic growth?" I am already working on that - on how we can manage the pricing of currency and on how we can manage money supply more precisely, allowing interest rates to find their own level.

If too much money is created then the new model for the economy - the new debt models will enable inflation of all incomes and prices to mop up the surplus without changing spending patterns or employment patterns. If we create too little money then interest rates will rise to the point here the economic growth rate slows.

When we print more money everyone should get their share. This can be done by using the new money to subsidise price and cost reductions across the board - a sort of post-Christmas sale to ensure that the economy stops slowing.

I am not convinced that there is any need for leveraged lending / fractional banking. It simply makes interest rates unstable and creates high instability in the accounts of lenders.

If too much money is created then the new model for the economy - the new debt models will enable inflation of all incomes and prices to mop up the surplus without changing spending patterns or employment patterns. If we create too little money then interest rates will rise to the point here the economic growth rate slows.

When we print more money everyone should get their share. This can be done by using the new money to subsidise price and cost reductions across the board - a sort of post-Christmas sale to ensure that the economy stops slowing.

I am not convinced that there is any need for leveraged lending / fractional banking. It simply makes interest rates unstable and creates high instability in the accounts of lenders.

APPENDIX

Gold Backed Currency or What?

Please observe that all experiments in different types of currency end with fiat currencies (money) being dominant.

What is the reason for that?

We can think:

A fiat currency as long as it is fiat and remains fiat (trusted), is easy to use, and is very versatile.

Its value is that it is a call on the income of others.

If anything does not call on the income of others does it have ANY value at all?

For example, Gold has a call on the income of others - how else would anyone buy it from you?

To be fiat it has to have a limited circulation

But to be of use there has to be enough of it to oil the wheels of the economy.

Whatever currency is chosen, supposedly fiat or not, it is ultimately a fiat currency - based upon trust - trust that it has a tradable value.

And whatever currency is chosen its value can and will vary because it depends for its value upon what people say it is worth.

When people negotiate their income it is a way of valuing money.

When people negotiate a price it is a way of valuing money.

If money is ultimately a call on the income of another or others, then it has a value that is measured in terms of average incomes. And those average incomes are the demand factor that drives average prices.

How does this sound?

If money is scarce its value rises and interest rates rise. If interest rises too much that means that money is scarce and the economy will not be fully oiled. This is the cue to create some more.

The question then is to whom does the new money belong? Constitutionally if I wrote the constitution it would belong to everyone as far as is practical.

At the same time I would look at the practicalities of distribution and of keeping the economy in balance, and so I would deviate slightly to ensure that the money went to people that spend, when they spend, and in proportion to that spending. The wealthy could spend more and get more new money than others somewhat in proportion to their wealth, but basically the idea is to promote sales of those items that are in demand and so to preserve and consolidate the existing spending patterns, not enforcing them, but more not changing spending patterns, and not putting jobs at risk. To some extent higher spending goes with higher wealth so if the wealthy get more by spending more that may help in this academic sense of perpetuating the current jobs that exist.

As explained in my book draft when spending patterns change with a lower proportion going on some things, and more on others, the deprived sectors suffer and jobs are placed at risk. I cited the time when oil prices fell and the world economy slowed as oil producers spent less.

What we need to do, so as to be able to cope with variations in the value of money, is to adopt new debt structures. These proposed new debt structures can change their costs in proportion to changes in the level of aggregate demand / average earnings / incomes. And at the same time the value to the lender / investor, which is the projected future call on income that the debt represents, can rise in the same proportion as everything else – prices generally to offset the fallen value of money. In this way, everything stays in balance. Spending and wealth are adjusted to compensate for the falling value of money relative to incomes / aggregate demand. In the absence of a similar increase in supply that is as it should be. How to do that?

I have it all worked out mathematically using a new equation that applies to all forms of debt and indicates not only that my recommended ILS Model complies with the conservation of spending pattern idea built in, but the ILS Model also minimises interest rate risk and property price bubbles.

http://ingram-school-illustrations.blogspot.com/

This is where Robert Shiller got stuck...he identified the problem of unstable property values / mortgage sizes, and saw that it sets an economy up for a crisis when asset prices inflate too far, but the solutions largely evaded him. It takes a book to solve that. My book:

http://macro-economic-design.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment